New Media Artworks: Prequels to Everyday Life

19 July 2009 / external, reference, thanksAs an occasional emissary for new-media arts, I increasingly find myself pointing out how some of today’s most commonplace and widely-appreciated technologies were initially conceived and prototyped, years ago, by new-media artists. In some instances, we can pick out the unmistakable signature of a single person’s original artistic idea, released into the world decades ahead of its time — perhaps even dismissed, in its day, as useless or impractical — which after complex chains of influence and reinterpretation has become absorbed, generations of computers later, into the culture as an everyday product. This story forms the core argument for including artists in the DNA of any serious technology research laboratory (as was practiced at Xerox PARC, the MIT Media Laboratory, and the Atari Research Lab, to name just a few examples): the artists posed novel questions which wouldn’t have arisen otherwise. To get a jump on the future, in other words, bring in some artists who have made theirs the problem of exploring the social implications and experiential possibilities of technology. What begins as an artistic and speculative experiment materializes, after much cultural digestion, as an inevitable tool or toy.

In other instances, we detect a whiff of outright theft. This may be difficult to prove, or at least, challenging to litigate, particularly for ideas which have simmered in the stew of the public domain for a few years. We simply pity, or perhaps snicker at, the artist who seeks redress from a behemoth corporation like Microsoft for its callous disregard of his Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.

Well, earlier this month, I experienced yet another day of cognitive dissonance in which

- I struggled to justify the value of new-media arts research to an audience of Silicon Valley businesspeople;

while simultaneously, - Some new-media artist friends of mine discovered that their work had been ‘appropriated’ by a large corporation.

There’s a clearly a cultural blindspot, here, folks. In the hope that these artists and others like them may receive some recognition for their pioneering prognostication and belated cultural influence, I here offer A few examples of New Media Artworks which Have Predicted the Future, Perhaps Too Successfully:

Myron Krueger’s Video Place (1974), and the Sony EyeToy (2003)

Myron Krueger (born 1942) is a pioneering American computer artist who developed some of the earliest computer-based interactive artworks. Krueger is also considered to be among the first generation of virtual reality and augmented reality researchers. Pictured at left is a scene from Myron Krueger’s landmark interactive artwork, Video Place, which was developed continuously between ~1970 and 1989, and which premiered publicly in 1974. Camera-based computer play begins here. The Video Place project comprised at least two dozen profoundly inventive scenes which comprehensively explored the design space of full-body camera-based interactions with virtual graphics — including telepresence applications, drawing programs, and (pictured here, in the “Critter” scene) interactions with animated artificial creatures. Many of these scenes allowed for multiple simultaneous interactants, connected telematically over significant distances. Video Place has influenced several generations of new media artworks, including some of my own (see, for example, my short essays, “Hands Up! The Media Art Posture“ and “Computer Vision for Artists and Designers“). By 2003, techniques for full-body camera-based interactions were considered inexpensive and reliable enough for mass commercialization. Pictured here, at right, is a screenshot of the Sony EyeToy, which was released in 2003 and has sold, according to Wikipedia, in excess of 10.5 million units. Today, the Sony EyeToy weighs a few ounces and costs just $29, and offers games featuring mass-market character properties (Harry Potter, Sonic the Hedgehog) and popular sports (basketball, football, Formula One racing, etcetera).

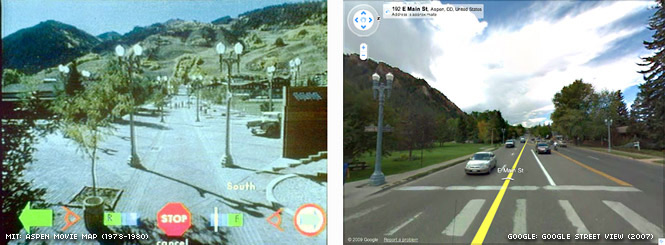

Michael Naimark & MIT ArchMac’s Aspen Movie Map (1978-1980), and Google StreetView (2007-)

Michael Naimark (born 1952) is a new-media artist and researcher interested in “place representation.” In addition to his influential work exploring cinema-based virtual and immersive realities, Naimark is also notable for his advocacy of media art as a stimulus for technological innovation — having directly helped establish a number of prominent research labs including the MIT Media Laboratory (1980), the Atari Research Lab (1982), the Apple Multimedia Lab (1987), Lucasfilm Interactive (1989), and Interval Research Corporation (1992).

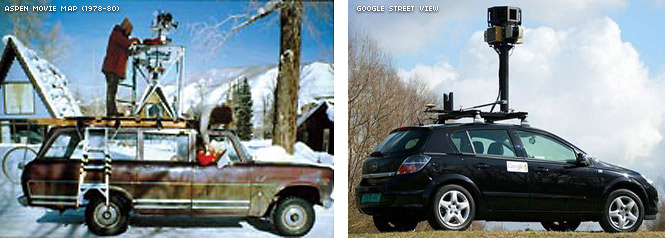

In the late 1970s Naimark was a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at MIT. Working in collaboration with Peter Clay, Bob Mohl, Andrew Lippman and others from the MIT Architecture Machine Group (“ArchMac”), Naimark helped create the Aspen Movie Map (1978-1980), a landmark hypermedia installation which allowed visitors to interactively explore and navigate the roads in a small town in Colorado. The Aspen Movie Map was made possible through an “artistic abuse” of the world’s first laserdisc player — namely, by taking a device which had been intended for the storage and playback of large movies, and instead using it for random access under interactive control. Naimark, who went on to create similar maps for more than a decade, says, “One could argue that the roots of two movements went through the Aspen Movie Map in the earliest days: the roots of multimedia and the roots of virtual reality.” More information about the Aspen Movie Map can be found at Michael Naimark’s web site for the project, including a remarkable video and some additional historic writings. Below are photos showing the automobile rigs used to create panoramas of the streets, then and now.

Built with financial support from DARPA, The Aspen Movie Map artwork was awarded the dubious “Golden Fleece Award” in 1980 by then-U.S. Senator William Proxmire — a sarcastic recognition he bestowed on projects which he felt were egregious wastes of taxpayer money. Nevertheless, the core ideas of the Aspen Movie Map live on, three decades years later, in Google’s widely-used Street View service (launched 2007), a feature of Google’s networked-based mapping tools that provides panoramic views of streets in more than a dozen countries around the world.

Jeffrey Shaw’s Legible City (1988) and E-fitzone exercise equipment (2008)

Jeffrey Shaw (born 1944) has been active in new media arts and research since the mid-1960s. Currently the director of the iCinema Research Centre at the University of New South Wales, Shaw was founding director (1991-2003) of the ZKM Institute for Visual Media in Karlsruhe, Germany. In 1988, Shaw and Dirk Groeneveld created Legible City, an interactive artwork with a sensor-enabled stationary bicycle interface, which allowed visitors to navigate and explore a 3D virtual environment by pedaling and steering. The work is well-known within the media arts literature, where it has been recognized for its advances in the poetics of immersive synthetic experiences and in the field of experimental physical interfaces.

Pictured above at right is a recent (ca. 2008) piece of digital exercise equipment from E-fitzone, a sports promotion “pilot lab” which purports to be Europe’s “first gym for interactive gaming”. An industry press article states: “According to Carla Scholten, director of Embedded Fitness, which initiated the project, ‘The idea for E‑fitzone was based on initiatives in the U.S. where a combination of gaming, entertainment and fitness training has become commonplace. It not only makes training fun, but also offers the option of creating an online account through which you can track your high scores, heart rate and energy consumption.'” It is difficult to judge from the photo, but the E-fitzone interactive cycling station appears to include a trigger-enabled joystick which Shaw’s artwork did not.

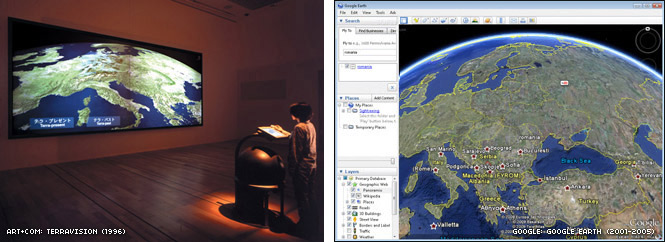

Art+Com’s Terravision (1996) and Google’s Google Earth (2001, 2005-).

Art+Com is a collective of German new-media artist/technologists, founded in 1988, which has since evolved into a small company providing custom interactive installation projects for clients in the industry, culture and research sectors. In 1996, Art+Com developed Terravision, a networked virtual representation of the earth based on satellite images, aerial shots, altitude data and architectural data. According to the Art+Com website, “Terravision was the first system to provide a seamless navigation and visualisation in a massively large spatial data environment. Users can navigate seamlessly from overviews of the earth to extremely detailed objects and buildings. In addition to the photorealistic representation of the earth, all kinds of spatial information-data are integrated, and are streamed into the system according to the user’s needs.”

Pictured at right is Google Inc.’s Google Earth, a “virtual globe, map and geographic information program” that “lets you fly anywhere on Earth to view satellite imagery, maps, terrain, 3D buildings, from galaxies in outer space to the canyons of the ocean.” Google Earth was originally called Earth Viewer, and was created in 2001 by Keyhole, Inc, a company acquired by Google in 2004. One significant difference between Terravision and Google Earth, is that the newer project takes advantage of user-generated cartographic annotations, allowing users to save their favorite places, and share these with others.

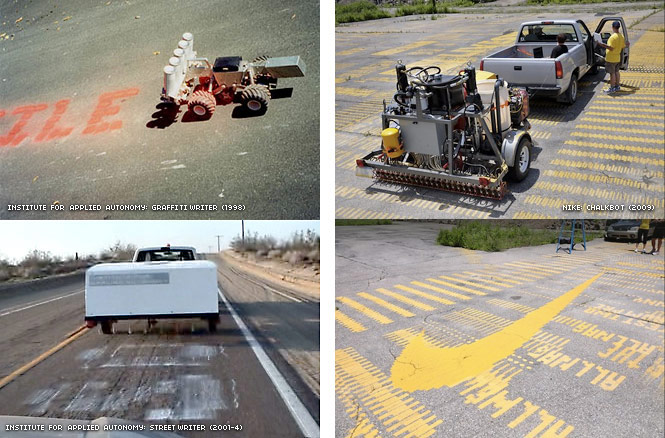

The Institute for Applied Autonomy’s (IAA) GraffitiWriter & Streetwriter (1998-2004),

and the Nike Chalkbot (2009)

It has sometimes been suggested that interactive new media art is propelled by two different strands of research: technoformalism, an inquiry which is primarily concerned with the aesthetic and experiential potentials of new technologies, and hacktivism, which is concerned with technology’s critical and sociopolitical possibilities. To the extent that technoformal artworks can be interpreted as neutral “media frames”, and are thus more easily adapted to commercial ends — as illustrated, perhaps, by the first examples in this article — it may be surprising and instructive to note that politically-challenging hacktivist work is not immune from such adaptations, either.

The Institute for Applied Autonomy (IAA) was founded in 1998 as an anonymous artist’s collective dedicated to the cause of individual and collective self-determination. For more than a decade, the IAA has created tactical media technologies, including various forms of “contestational robotics”, which are intended to extend the autonomy of human activists. In 1998 the IAA developed GraffitiWriter, a small “tele-operated field programable robot which employs a custom built array of spray cans to write linear text messages on the ground at a rate of 15 kilometers per hour,” whose “printing process is similar to that of a dot matrix printer.” GraffitiWriter provoked controversies on a number of occasions; for example, during an award ceremony on live Austrian television in 2000, at the height of Austrian governor Jörg Haider‘s xenophobic campaign against immigrants, GraffitiWriter went scandalously ‘off-script’ and printed the activist slogan Kein mensch ist illegal (“No person is illegal”).

IAA’s subsequent project, StreetWriter (2001-2004) consists of a substantially larger computer-controlled industrial spray painting unit that is built into a van or trailer. The system is capable of printing text messages hundreds of feet long, and as wide as a lane of traffic. StreetWriter was developed in order to protest the militarization of robotics and the privatization of public space through corporate messaging. In 2004, for example, the project was deployed in protest of the first DARPA Grand Challenge, where it printed Asimov’s first rule of robotics (“A robot must not kill”). Video of the IAA StreetWriter can be seen here.

In mid-2009, the sports apparel manufacturer Nike and its PR agency, Wieden+Kennedy, commissioned Pittsburgh design studio DeepLocal to create a similar device, Chalkbot, for use in its “LIVESTRONG” advertising campaign for the 2009 Tour de France. The Chalkbot system was used to print inspirational messages sent (via SMS and the Web) by Internet users, as well as Nike’s campaign slogans and logographs. The Institute for Applied Autonomy group was not involved in (or informed about) Nike’s appropriation of its Streetwriter concept, and posted a press release stating their objection to “the corporate appropriation of ‘outsider’ research projects without acknowledgement of the amateur, collective, hobbyist, and activist communities upon which projects like Chalkbot are built.” Deeplocal posted a response to this, asserting the value of Chalkbot for spreading messages of hope for cancer survivors, and more generally for connecting a very large public, so directly, to such a messaging device.

Chris O’Shea’s (IAA) Hand from Above (2009), and the Forever21 Billboard by Space150 (2010)

In autumn 2009, British new-media artist Chris O’Shea was commissioned by FACT (Foundation for Art & Creative Technology) and the Liverpool City Council to create an interactive public artwork for the BBC Big Screen Liverpool and the Live Sites Network. His project, Hand from Above, featured the hand of an enormous and mischievous “deity” which appears to tickle passersby, pluck unsuspecting pedestrians out from their surroundings, and perform other whimsical actions. Hand from Above premiered on 23 September 2009 during the inaugural Abandon Normal Devices Festival, and in May 2010 was awarded an Honorable Mention for interactive art in the Prix Ars Electronica, the world’s largest, best-known, and longest-running competition for experimental computer arts. Hand from Above has since been shown in Tokyo at Roppongi Art Night, at the invitation of the British Council Japan and Mori Building. Subsequently…

On 25 June 2010, a new interactive billboard went live at Times Square in New York City. Designed by interactive agency Space150 for Forever 21, as announced by industry magazine FastCompany.com, the billboard featured “a model walking in front of an image of the crowd below. And then it gets interesting: The model occasionally leans over, and appears to pluck someone out of the crowd. Sometimes, they stink, so she tosses them.” (This interaction is pictured above.) “It’s an over-used expression, but this really is cutting edge technology,” said James Squires, director of technology, Space150. “Computer vision is … very new and it’s going to be incredibly effective when Times Square shoppers find themselves being picked up by giant models.”

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to the artists listed above, all of whom, in full disclosure, are friends or acquaintances. I’m also grateful to Eric Paulos, who alerted me to some important examples, and to the many others online who responded to my request on Twitter for similar instances. I learned that there are many, many examples of new-media artworks which laid the conceptual groundwork for everyday commercial products. (Want some more? How about Motoi Ishibashi and Motoki Kouketsu, whose G-Display artwork (1999) anticipated most modern tilt-based interactions. Or contrast Camille Utterback and Romy Achituv’s well-known media-art classic, Text Rain (1999), itself a descendant of Myron Krueger’s Video Place, with the new Word Wall “donor recognition system” (2009) by SnibbeInteractive.com.)

There’s also another question I’ve left unaddressed here, which concerns the shifting artistic (as opposed to economic) value of artwork-inventions which become commonplace tools and products. These stories are ultimately, for me, inspirational yet grimly depressing — and so for now, I’ll let the bittersweet job of making a comprehensive list of such projects fall to someone else.

« Prev post: Pedagogic Resources on Chinese Painting Villages

» Next post: Golan’s 2009 TED Talk, online